Statewide Fare Relief for Low-Income Riders

Our Goals

To pay for fare relief for low-income riders statewide for a year, by allowing SNAP-eligible transit riders to show their EBT cards in lieu of fare payment. U.S. jobs are not anticipated to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2024, and transit riders are some of those hardest hit by the pandemic’s economic impacts. Transit agencies are not projected to “return to normal” before 2023, so there should be sufficient capacity to accommodate increased ridership without requiring additional transit operating funds or service.

To fund the evaluation of the impact of the fare relief program, so that the state and local transit agencies can assess the value of implementing long term low-income fare programs. We will incorporate the cost of funding that research into our statewide call, including staff costs at the research institutions, and incentives for transit riders to report on critical metrics. These metrics could evaluate how travel behavior changes because of the fare relief, and how free fares support low-income riders’ ability to pay for other critical needs.

What is the problem that fare relief solves?

Transit fares inhibit low-income people from access to critical needs, including jobs, food, healthcare and other social services. They force low-income people to negotiate between multiple critical expenses, and to ration their trips. Transportation costs are households’ second largest cost burden, and data from the Bureau for Labor Statistics show that people earning between $5,000 and $30,000 per year spend 24 percent of their income on transportation. In the Calgary study of a 50% low income pass, 13% of low-income pass holders indicated they couldn’t otherwise pay for a transit pass, 48% said that the $37.50 would come out of their household food budget. A study of Chester County PA which found transportation costs (specifically public transportation) were a major concern for obtaining food.

Transit ridership is down to 35% of pre-COVID levels.

Pennsylvania needs targeted investments to improve public health and to stimulate an economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic. The impacts of the pandemic have been disproportionately borne by low-income households and people of color, who are also those that are disproportionately reliant on public transit.

Low-income riders in the Pittsburgh region have become increasingly dependent on public transit over the past decade, even as their access to transit has become more limited due to the affordable housing crisis.

Philadelphians spend more of their income on transit fares than riders in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington DC, Seattle, and San Francisco. Philadelphia has the lowest minimum wage in the US.

Evidence of Benefit of Low-income Fare Programs

Low-income fare programs have resulted in improved employment, food access, social service and healthcare access. This Toronto study demonstrates that low-income riders’ ability to do all manner of critical activities more than doubled even with a limited fare reduction. The MIT low-income fare study reported following benefits from 50% fare reduction:

- Riders with the fare discount took about 30% more trips.

- Riders took more trips to health care and social services.

Transportation emissions are one of the largest contributors to climate change, and low-income fares can reduce greenhouse emissions by up to .3%.

Public transit generates enormous economic benefits in PA, including in rural regions. For Pennsylvania, the Benefits-Cost of investing in transit in rural and small urban areas is 1.86. The Calgary low-income fare study assessed the social value of a low-income fare program and found a one year weighted SROI average of $1: $12.25.

This is in line with proposals being implemented and explored in major cities across the United States. Transit agencies that have implemented free or reduced fare programs during the pandemic (this is not an exhaustive list of cities that have had low-income fare programs in place since before the pandemic):

- Bay Area transit agencies are using CARES Act money to expand low-income fares.

- Los Angeles Metro is planning to institute free fares for low-income riders and students in Jan 2022, and to transition to a fully fare-free transit system.

- Seattle Transit Systems have expanded their low-income fare programs during the pandemic.

- DC Metro is undertaking a study to evaluate free transit for low-income riders, and possibly transitioning to a fully fare-free system.

- NYC has implemented their low-income fare program during the pandemic

- Richmond’s Transit Agency voted to continue fare free transit through the duration of 2021, and Detroit’s Transit Agency has not returned to collecting any fares since implementing rear door boarding and free fares after the pandemic began.

- Valley Transportation Authority Santa Clara County reinstated free fares in February 2021.

Low-income fare support or recommendations for Pennsylvania Transit Systems

Statewide recommendations: The Governor’s Workforce Command Center report identified transportation as the #1 key barrier to accessing jobs, with one of the recommendations stating the following:

“Increase awareness of transit subsidies [Public Sector]: The commonwealth should support low-income commuters by making sure they are aware of reduced-fare programs where they exist, and if possible, expand the number of individuals who qualify for reduced fares or further reduce the fares for those who qualify. Expanding public transit subsidies for individuals lessens the financial burden that employees face when commuting to work. In addition, increased awareness for public programs that provide subsidies or reduced fares for low-income populations could increase the use of transit options.”

Pittsburgh region

- Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership [Downtown Mobility

- Plan](https://downtownpittsburgh.com/mobilityplan/) recommends low-income fares to support mobility and equity in the downtown corridor

- The Pittsburgh Food Policy Council Greater Action Plan names advocating for transportation to be more affordable for low-income riders as a priority action item.

- The City of Pittsburgh Department of Mobility and Infrastructure identifies low-income fares as a priority intervention to support people to weather the COVID-19 storm.

- Port Authority CEO Katharine Kelleman said in May, 2020 “We have been very clear that we are looking at a low-income fare, but we have to make sure it is useful and durable. There is a great need now.” Also on the WESA’s The Confluence CEO Kelleman said in Oct 2020: “If we have an entity willing to help cover the cost of those fares, we would be very interested in piloting a program. And a pilot would be great because then our passengers could use this, kick the tires, and tell us what works and what doesn’t.”

- Senators Jay Costa, Lindsey Williams, Wayne Fontana, Pam Iovino, and Representatives Ed Gainey, Sara Innamorato and Summer Lee along with local legislators signed a letter to the Port Authority in the summer of 2020 calling for fare relief for low-income riders using EBT cards.

- In July 2020, Allegheny County Council passed a motion on the Port Authority to implement fare relief for low-income riders to address the crisis of the pandemic.

Philadelphia Region

- PEW report on inequitable distribution of SEPTA fare costs and high cost burden for low-income residents

- The City of Philadelphia’s Office of Transportation and Sustainability identifies implementation of a low income fare program as a top goal to improve transit usage and equity.

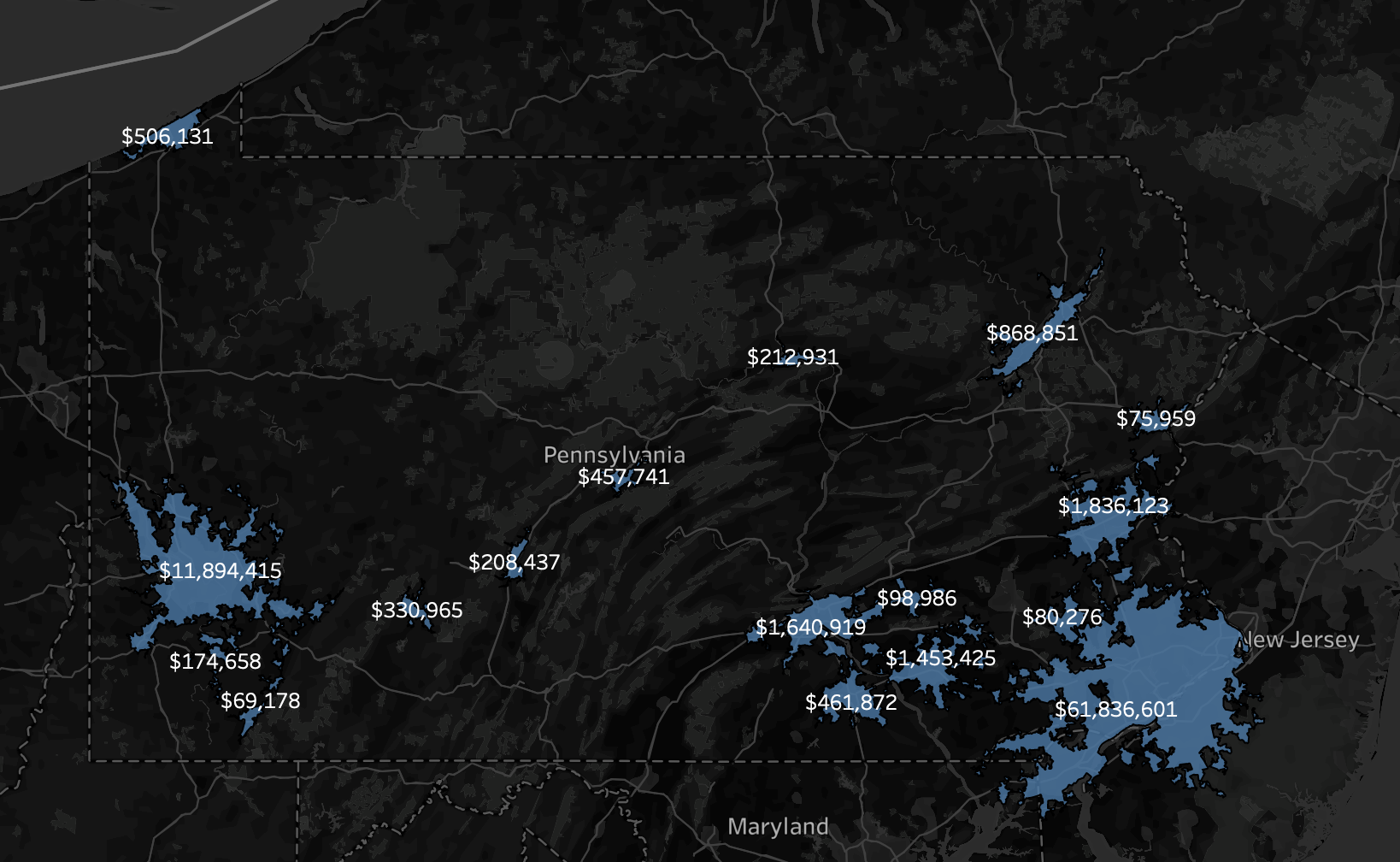

How much would a year’s worth of fare relief for low-income riders cost statewide, for fixed route transit, if riders would show EBT cards to board?

$82,207,468, with an additional $8,800,000 to support an evaluation of the impact of the program, for a total cost of about $90,000,000.

Why are we calling for a low-income fare program that allows transit riders to show EBT cards to board transit?

EBT cards are an existing, very effective social service program that will capture most of the folks with the highest need. There would be no operating costs for transit agencies to implement, and would not require any additional administration, so it could be instituted almost immediately.

This is a low cost, high benefit targeted intervention to address the economic and public health crisis, and help jump-start transit systems in their pandemic recovery.

How would we measure the benefit or impact of the program?

Partner with a research institution to commit to running a study like the MIT/MBTA study (with on-going rider engagement to assess how the low-income fares increases their ability to access critical needs), but statewide. Nelson/Nygaard study looks at the San Francisco possibilities for low-income fare, but specifically evaluating ridership and agency cost impacts of different low-income fare program scenarios.

Ask transit agencies to agree to share ridership and EBT usage data with that research institution, and to post advertisements on their buses to recruit riders to participate in the text message evaluations.